Catalogue essay (published in English and Mandarin) for the solo show of Ting Ting Cheng, ‘Object Fantasy’, at Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, summer 2011.

Joanna Zylinska

Language games

-- We only ever speak one language...

(yes, but)

-- We never speak only one language...

(Jacques Derrida, The Monolingualism of the Other)

Ting Ting Cheng, Things We May Never Know

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida, known not only for his prolific contribution to philosophical debates on metaphysics and language but also for his legendary seminars and lectures, delivered with equal aplomb in French and English, opens his book, The Monolingualism of the Other, with what may sound like a surprising confession: ‘I am monolingual. My monolingualism dwells, and I call it my dwelling; it feels like one to me, and I remain in it and inhabit it. It inhabits me. ... It is me’. What Derrida means by this is something else than a lack of language skills on his part. It is rather the recognition of the difficulties involved in going beyond what the linguists call our ‘first’ language, but also the difficulties involved in even using this ‘first’ language, which is supposed to feel more ‘natural’.

Our first language comes to us when we are children; it is a gift we receive from others (even if we cannot exactly remember the moment of its reception) and then gradually make our own. Indeed, what Derrida is signalling in the quote above is the foreignness of language as such, if by language we understand an attempt to break through the solipsism of the self and reach out to the other -- to commune and communicate with him or her. Derrida admits as much himself when he says: ‘it will never be mine, this language, the only one I am thus destined to speak’. There is something profoundly brave but also perhaps profoundly tragic in this recognition by the great wordsmith Derrida that language always escapes him -- that, paradoxically, linguistic communication which is by its nature communal is nevertheless a lonely activity. It is something that is bound to leave us speechless, literally lost for words.

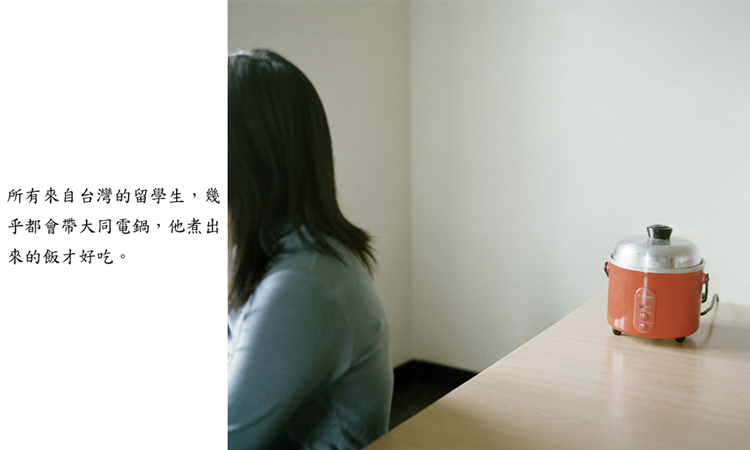

Ting Ting Cheng’s photographic art practice seems to emerge precisely from the recognition of this linguistic paradox, offering as it does an apt illustration of what we could describe as ‘polyglot monolingualism’. Arguably, due to its representational ambitions, photography is a medium ideally placed to explore the constructed nature of linguistic communication. Cheng skilfully navigates between the visual and oral representations of foreign languages: she offers us beautifully printed captions in foreign alphabets, teases us with book pages we are unable to read, and offers re-mediated recordings of her own linguistic efforts while on a residency in Spain. In her work English, Spanish, Mallorqui, Korean and Mandarin intermingle, offering viewers a dizzying journey into the Tower of Babel the contemporary globalised world has become. Ironically, it is in the supposedly transcendent symbolism of the global brands -- the Nike swoosh, the Louis Vuitton LV monogram (as evidenced in her ‘Still Life with Fruits’ series) -- that some kind of cross-cultural communication can occur today.

Ting Ting Cheng, Still life with Louis Vuitton Bananas (in Baroque style)

Faced with Cheng’s work, viewers may find themselves puzzled, lost, struggling for comprehension, with all languages -- including that original ‘first’ language that was supposed to serve them as a stable anchor point -- also suddenly becoming ‘foreign’. Yet, in introducing linguistic confusion, Cheng’s images simultaneously develop a language of their own, conveyed through the elegance of their form and design, the pastel colours, the subtle use of soft focus. In this way, her photographs become low-tech ‘communication devices’ in their own right, which successfully compete with ubiquitous media gadgets such as mobile phones. They also function as receptacles for playing out and managing the anxieties of individual and global miscommunication. Indeed, in Cheng’s work aspects of failure inherent in the communication process are brought to the fore and then carefully worked through, beyond frustration and beyond any desire to comprehend and thus master the whole world. We could perhaps go so far as to say that, through her art work, Cheng outlines a modest ethics of misunderstanding, celebrating our monolingualism that always, inevitably, makes us foreigners in the world, no matter how well-travelled and linguistically skilled we are.